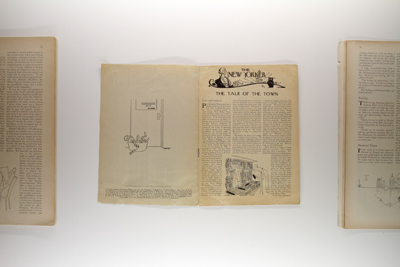

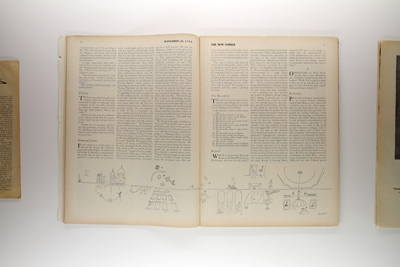

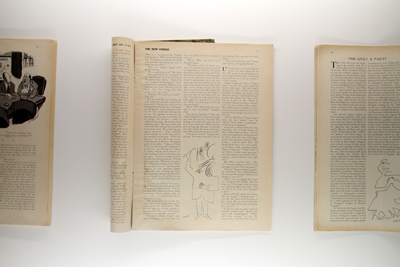

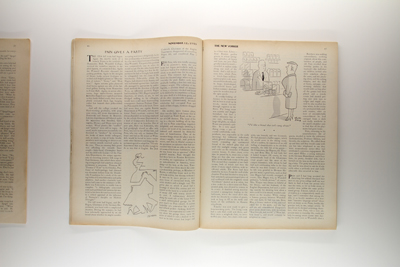

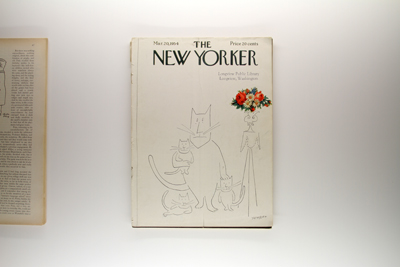

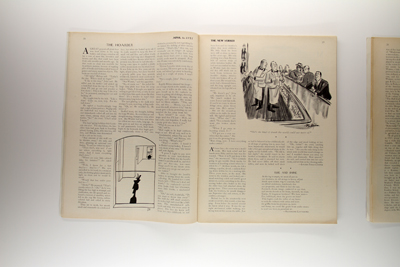

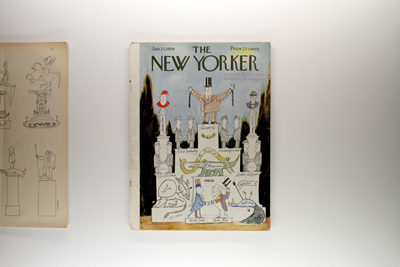

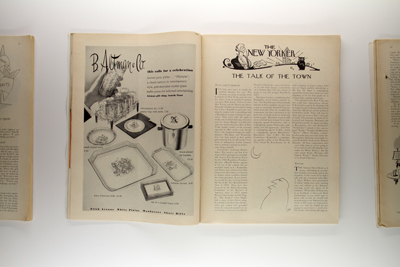

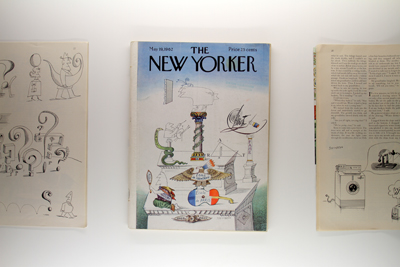

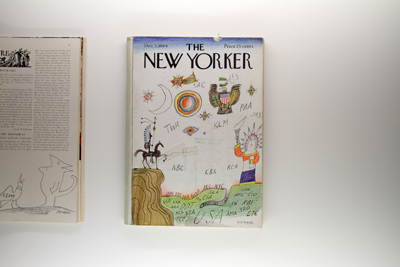

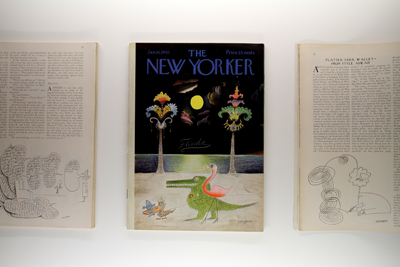

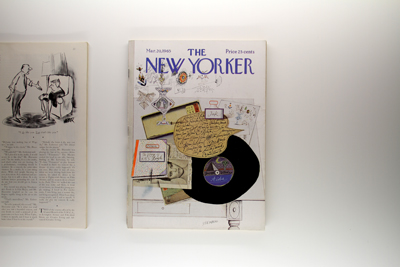

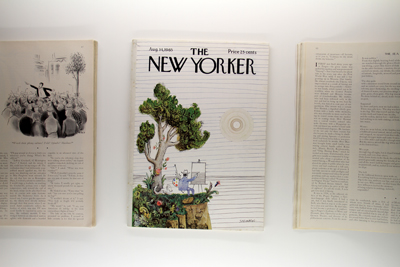

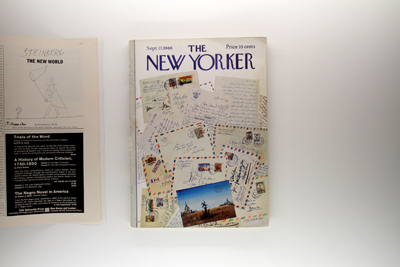

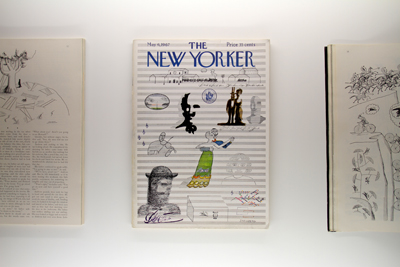

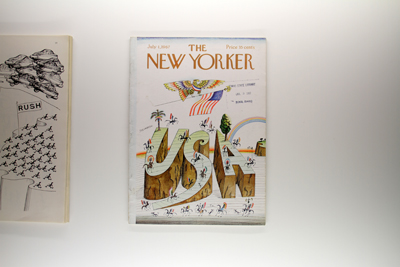

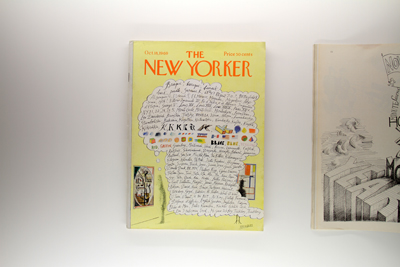

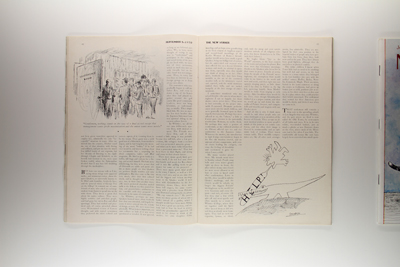

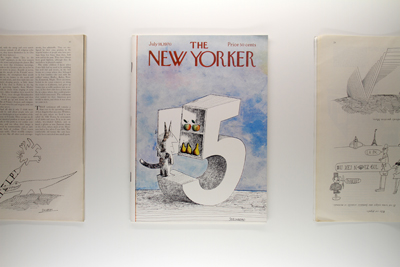

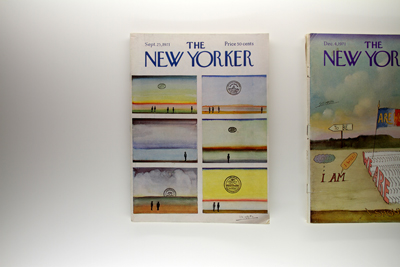

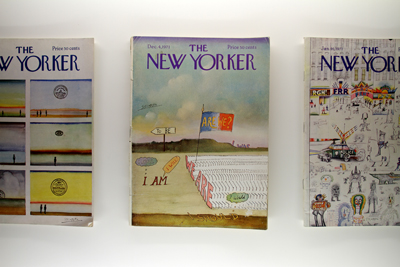

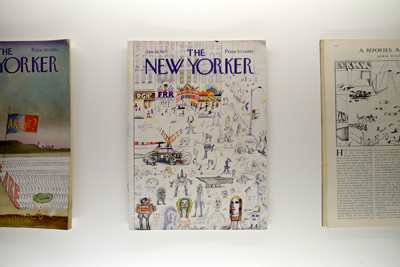

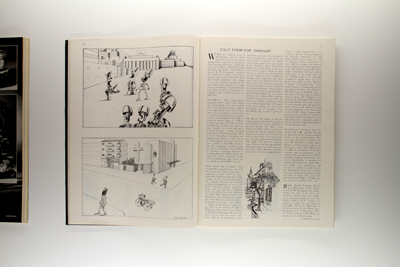

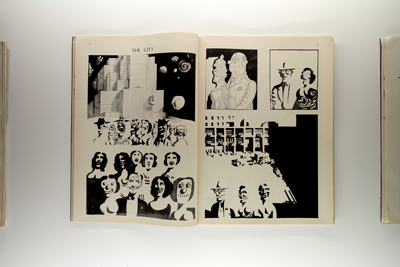

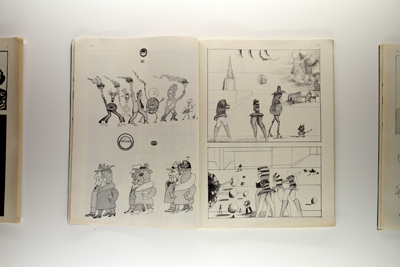

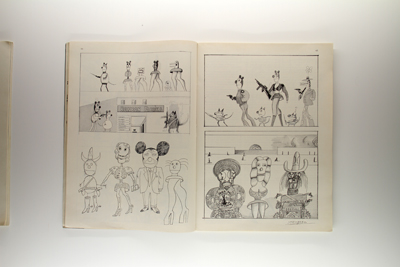

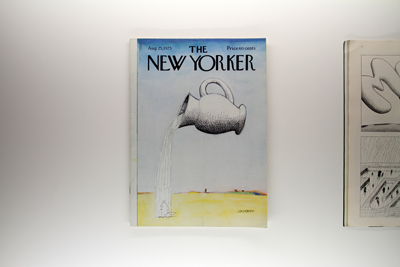

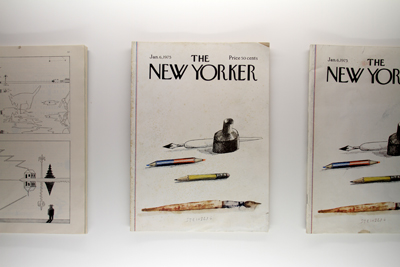

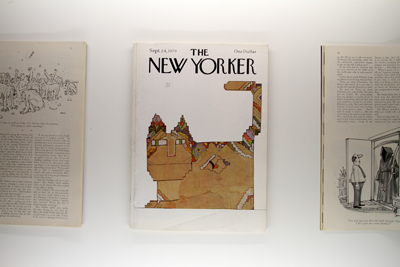

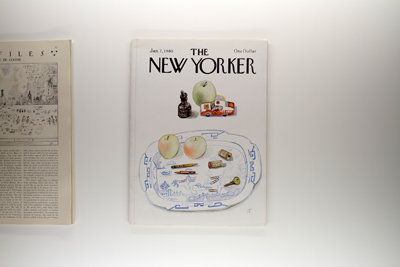

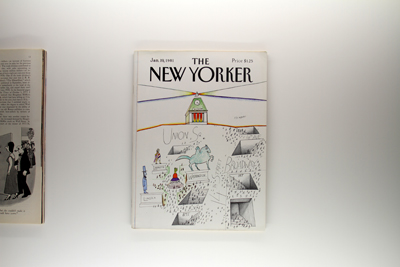

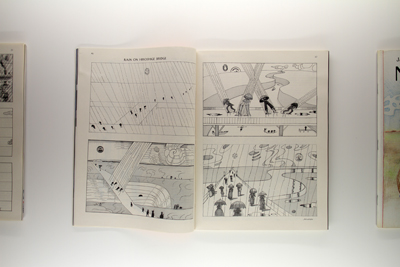

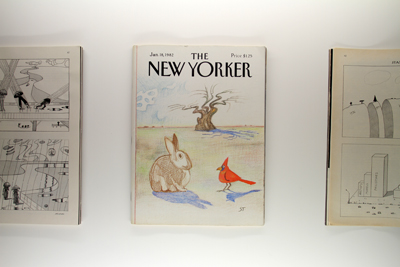

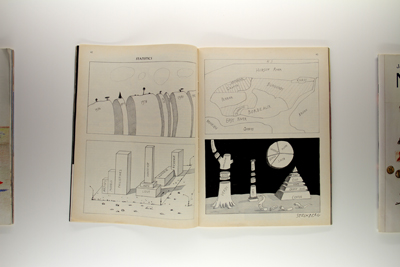

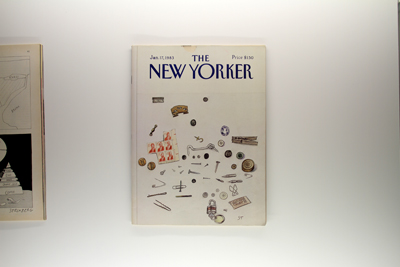

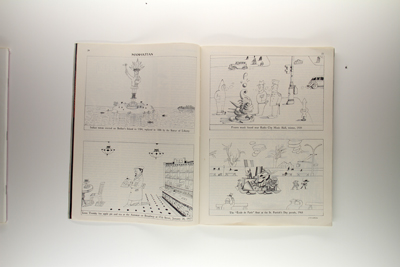

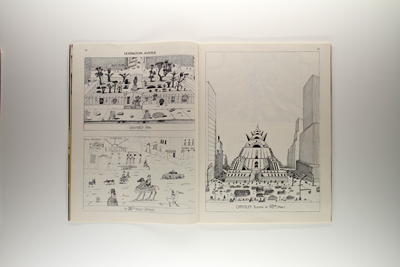

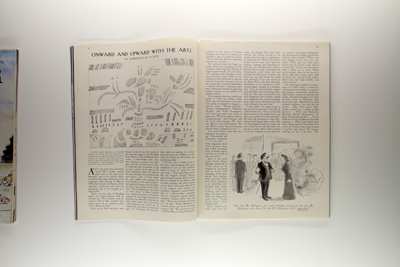

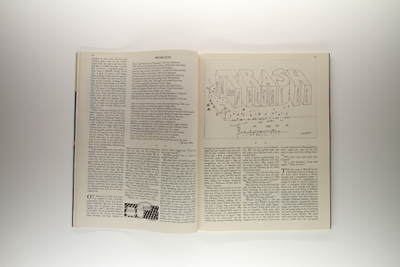

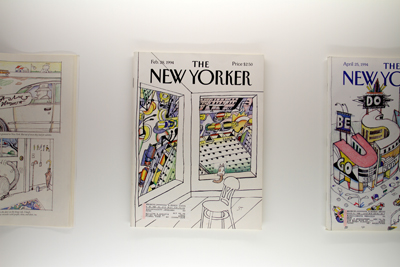

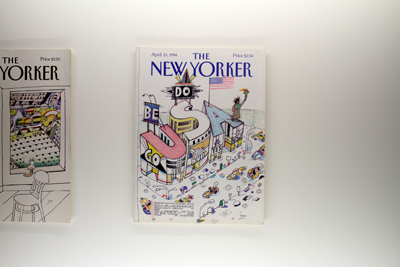

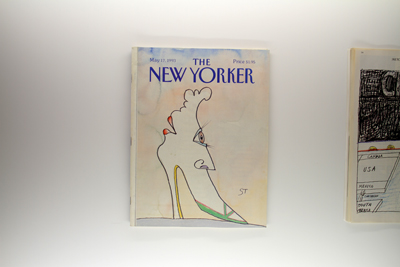

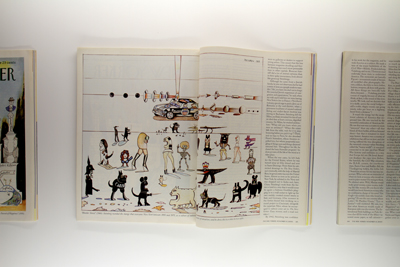

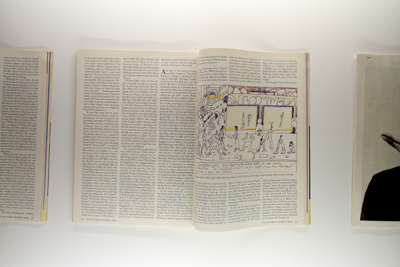

STEINBERG, SAUL. THE NEW YORKER. NEW YORK, 1945–2000. (HAROLD, WILLIAM, ROBERT, TINA, DAVID, EDS.)

An Exhibition

June 16–August 10, 2012

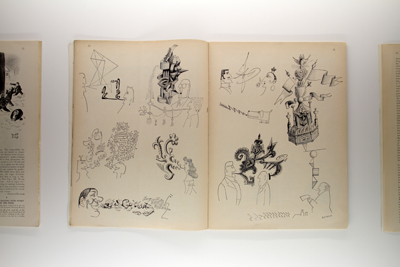

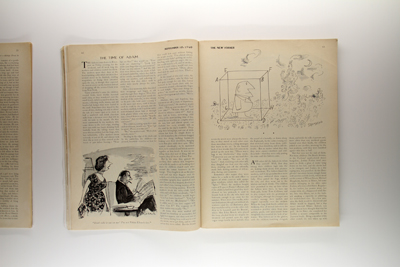

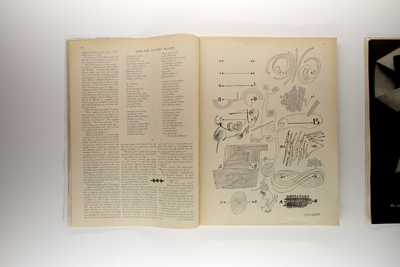

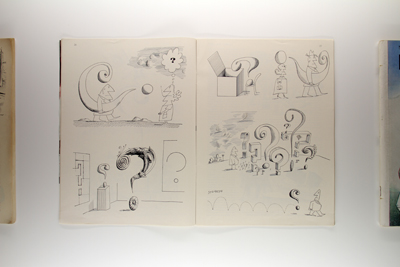

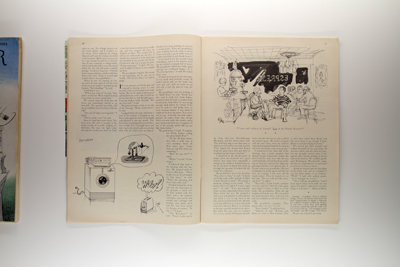

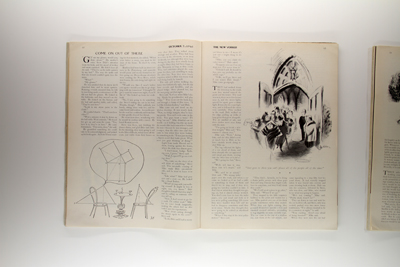

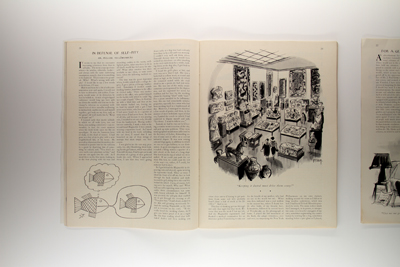

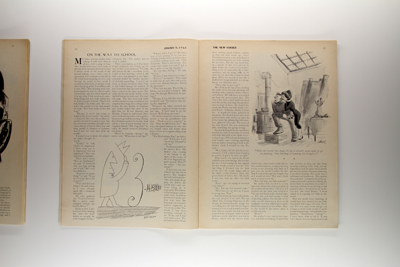

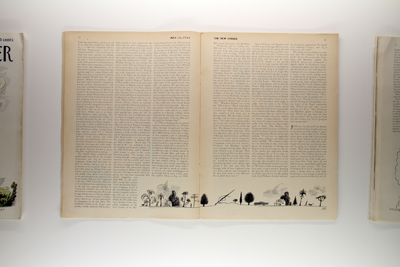

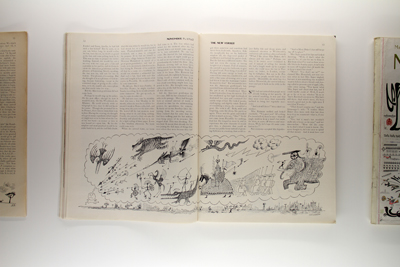

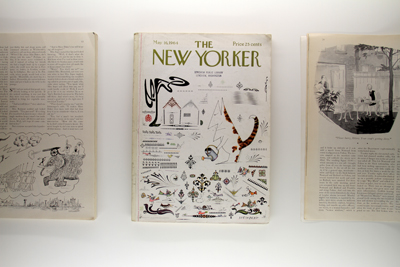

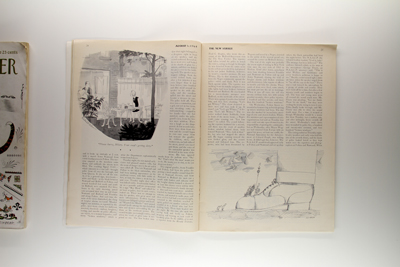

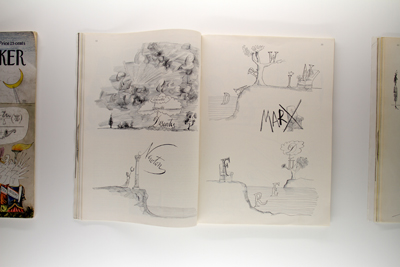

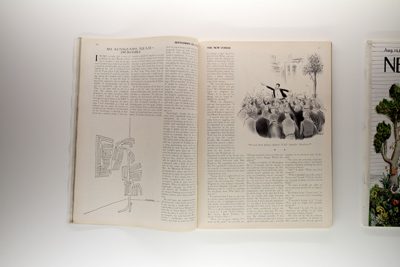

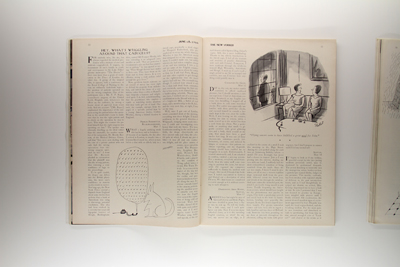

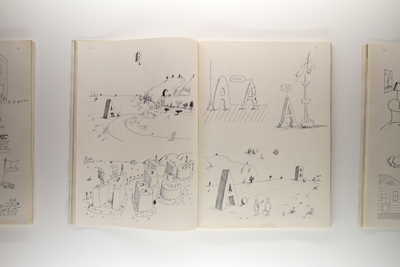

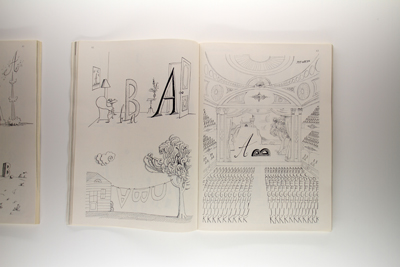

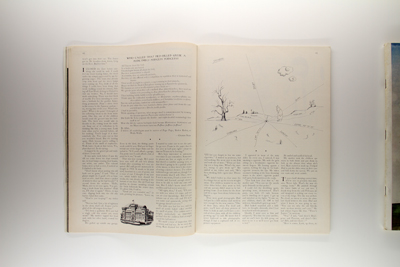

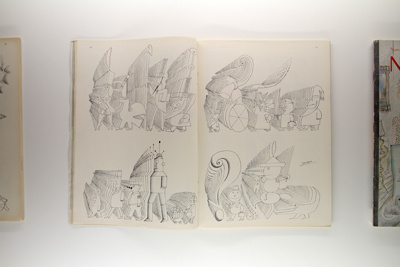

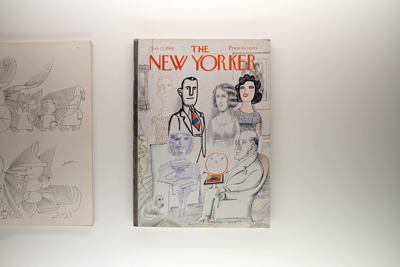

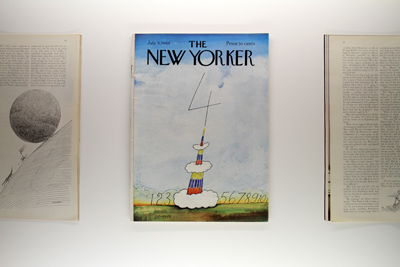

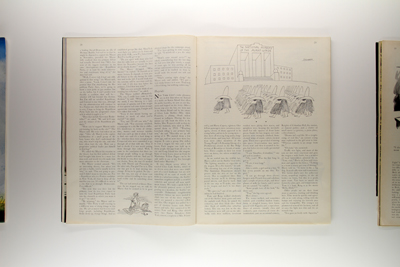

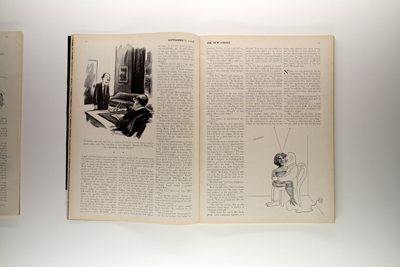

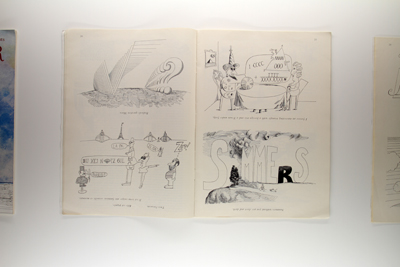

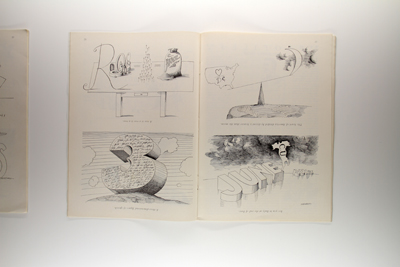

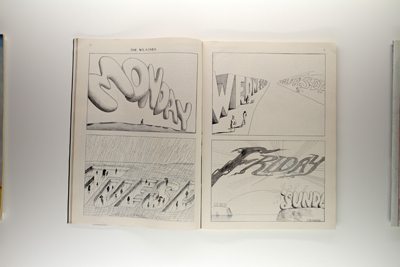

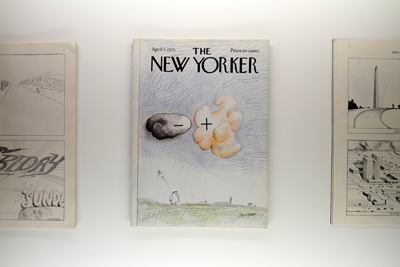

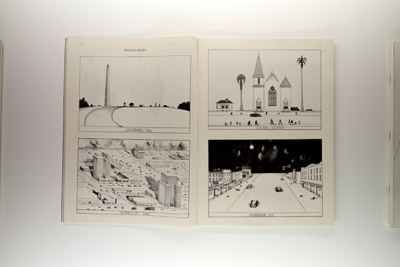

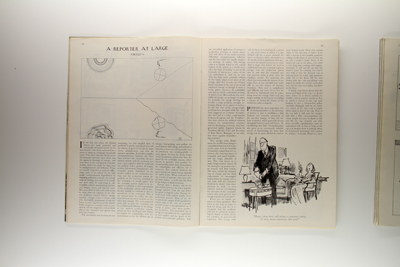

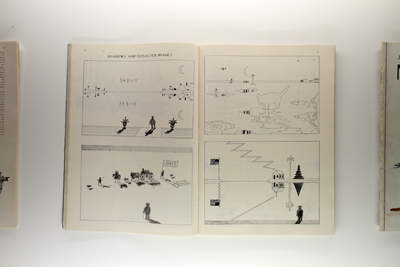

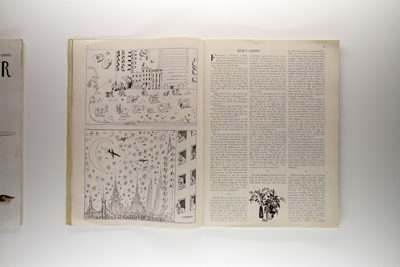

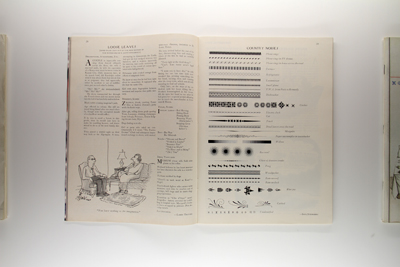

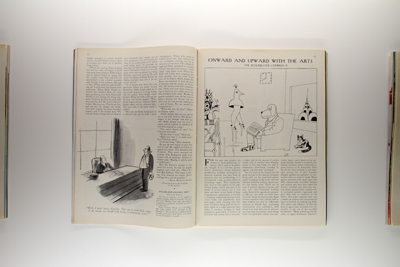

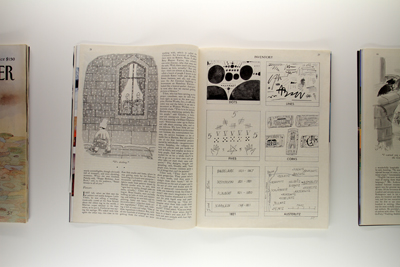

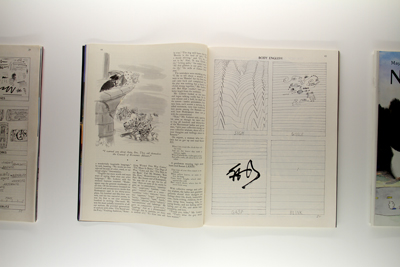

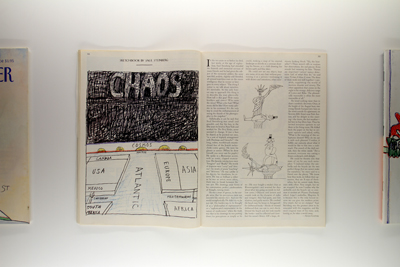

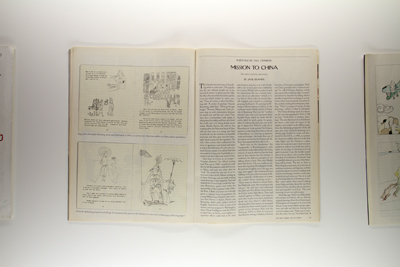

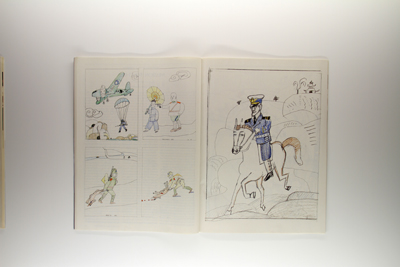

“For more than fifty years, Saul Steinberg was The New Yorker’s nonpareil sketcher, observer, spy and—though he would have thought the word dingy and depressing—its chief cartoonist, too. But then he disliked being called an artist, too, since it called to his mind the salon-swindle of ‘exciting’ objects and collectors’ manias. ‘All of those drawings, whimpering at night in the wrong houses,’ was his dry description of the consequences of selling pictures to collectors, rather than publishers.”* Whatever he is, this exhibition, naming The New Yorker’s consecutive editors, collects some two hundred of his one thousand published contributions, presented as is: magazines, collected through time, some slightly yellowed and hung with that irrevocable library smell, (Longview Public Library, October 22, 1955) and others, mint (V.G.+, no marks, no ears, no creases), en-sleeved and collected with breathy fandom.

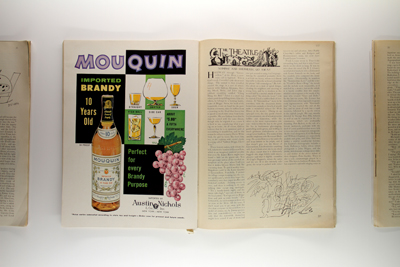

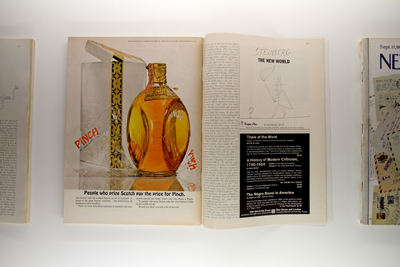

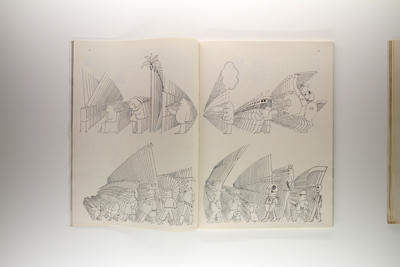

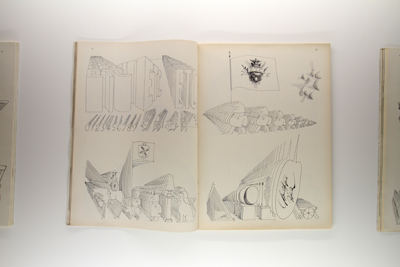

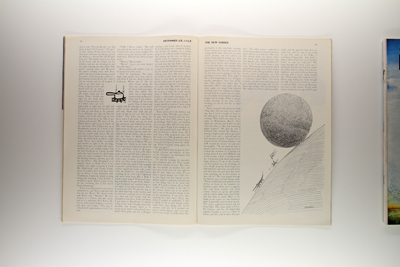

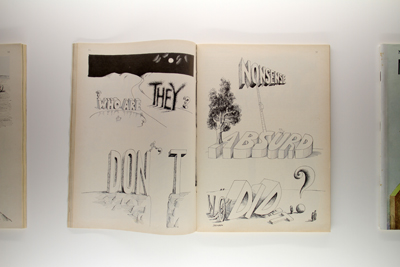

If there is a way to think about Steinberg without thinking about the magazine itself, its distribution, advertising, reputation, the dense thicket of Marshall McLuhan adage (old clothes upon old bones), and the bloodless and goofy-footed ghost of Walter Benjamin, then we are blind to it. We can’t imagine how you could see Steinberg’s stenographic line without seeing the page it is on. “Everything has a message,” Steinberg noted, “even the smell of museums. In Europe, museums smell of town halls and grade schools; in America they smell like banks.” The circulatory system has a message, the page has a message, the ads have a message, the neighborhood of fiction and news have a message, all of it makes for juxtapositions as eerily apposite as anything the French surrealists or a blender could come up with. Libido-heavy Masterpiece pipe tobacco banners and pre-ironic ads for J.L. Hudson Vycron® polyester pant-suits running opposite a Steinberg, a Sylvia Plath poem, and a paragraph where Harold Rosenberg pours cold gravy over some poor painter’s heart. But perhaps we’ve left it soft. Sailed in, coveted the shell and neglected the pearl. So we’ll drop this spoon in hopes that you’ll think sometimes of other lovely things.

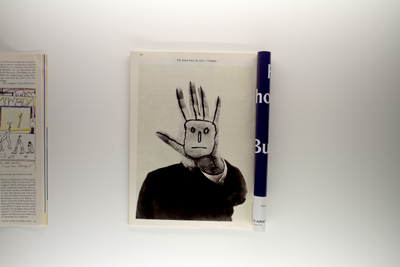

As a matter of biographical fact, Saul Steinberg (1914–1999) was a misfit. Born in Romania, European to the bone, he made little of his origins; “pure Dada,” he called his native land. He studied and made his artistic beginnings in Italy, receiving in 1940 a doctoral degree in an architecture he never practiced. Steinberg was shaken out of a congenial life by the turbulence of politics and war, and cast to America in the 1940s where he lived strung up between the uninteresting and unfortunate binary of Artist v. Cartoonist.

There are teachers and students with square minds who are by nature meant to undergo the fascination of categories. For them, zoological nomenclature and taxonomy are everything. But good thinkers, the ones that outlive their own historical circumstances, are always much more complicated than the rhetorical truths we have about them. And that’s what we like most about Steinberg. We like the absence of the-world-as-represented-by-anybody-else.

What would impel anyone sound of mind to leave the absence of the-world-as-represented-by-anybody-else for dry, familiar land? We still don’t know. Yet how to account here for our overriding need to write and track the absence of the-world-as-represented-by-anybody-else—to do that, just that, only that, and consider it as rational an occupation as riding a tricycle over the Alps?

*Gopnik, Adam. “Saul and the City.” In The Guardian (Nov. 26, 2008).

During his lifetime, Steinberg’s work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Smithsonian Institution.

The exhibition program will include a talk by Stuart Bailey of Dexter Sinister on Tuesday, July 3, 7pm; a screening of Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin on July 24, 8pm; a lecture by the exhibition coordinators Robert Snowden and Scott Ponik, Tuesday, July 31, 7pm; a screening of The Right Way by Fischli and Weiss on Thursday, August 9, 8pm. The exhibition will travel in September 2012 to Artspace, a non-profit institution in Auckland, New Zealand.

An alternative here: (6.4 MB)

“Alas,” said the mouse, “the world is growing smaller every day. At the beginning it was so big that I was afraid, I kept running and running, and I was glad when at last I saw walls far away to the right and left, but these long walls have narrowed so quickly that I am in the last chamber already, and there in the corner stands the trap that I must run into.” “You only need to change your direction,” said the cat, and ate it up.

A story by Franz Kafka. Its English title is “A Little Fable.”