HARTMUT BITOMSKY

Dust

Germany, 2007, 35mm, 90 min.

A Screening and Talk as part of THE DEVIL,…

Saturday, January 18, 4pm at NWFC

The film will be introduced by the filmmaker.

“The films I make are about objects: big, extensive, and complex objects. Objects that exist as points, if you will, at the intersection of numerous vectors. Made by people, these objects show the traces of human activity in forms of collective effort and conflict. Oddly, in my experience, these traces remain indistinct and confused when you make humans the direct subject of the film. Individual biographic documentary can shut out certain oddities, human tics, and parts of testimony.

“In the past, when the shutter speed of the camera was slower, a stabilizing device was needed behind the subjects to anchor them in place so that a portrait could be taken. Without these devices, the subject’s uncontrollable movements would have prevented a clean, stable portrait, and instead little fogs would have been exposed onto the film. In a way, I make films about these stabilizing devices, showing people more as a social category rather than individuals. In a way, the device reveals some traits and proportions of human conditions better than it reveals individual humans. In the films, people are studied just as motionless dolls or puppets are in anatomical drawing classes.

“With the subject of dust I went one step further. Dust is matter constantly worked on by people—physically, practically, mentally, theoretically, metaphorically, scientifically and medically, but the material properties of dust are such that neither a structural device, a mechanical contour, or a full, lasting vector are formed in our scrutiny of it. The shape of dust is always provisional, it never turns into a final product of human activity, it remains a thing without specific form or function.

“Our final physical facts become visible when observing dust in the way a shape becomes visible in the negative of a casting mold. This project is a philosophical one about a refined, and insignificant aggregate state of matter. For me the challenge was to make the object visible at all. In the face of dust all tools and means more or less fail, and the film becomes a crisis and critique of perceptions. This is of course an exciting situation for a filmmaker. The challenge was to keep up and deepen this suspense, as if it were a thriller which set out to investigate an elusive enemy.”

Hartmut Bitomsky was born in 1942 in Bremen, Germany. Bitomsky is also a great film critic and educator. He attended the Free Unversity Berlin and the Berlin Film Academy, where he was expelled with HARUN FAROCKI for political activism.

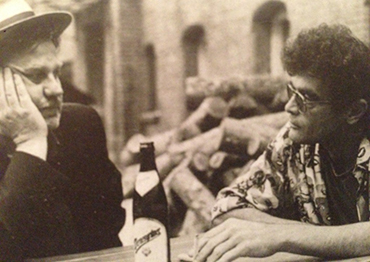

Hartmut Bitomsky and Harun Farocki, 1993

“For more than ten years, he co-published and edited the German publication Filmkritik. The journal published 12 issues a year; a demanding schedule which obliged the 12 to 15 editors to regularly contribute texts that were more often complex essays than reviews. Filmkritik’s high point came at the end of the 70s when the journal devoted an entire issue to Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958) and another to the work of Peter Nestler. In both cases, the Berlin editorial team watched and discussed all the films together; a single author or a group would then write a text which was collectively discussed and rewritten; the process continued until the special issue was completed. […] In retrospect the journal had reached an impasse by the mid 80s; the 10-year boom in film production in Germany had failed to generate an equivalent excitement around film discourse; Filmkritik found few directors and writers willing to join them in their search for a new critical language. Their response was to demand more commitment from their contributors; they dismissed people such as Wenders who only wrote occasionally and became a sect whose standards intimidated the kind of authors they would have needed. To read Filmkritik today is to perceive the value of support structures and elective affinities. The debates and conversations obliged editors and contributors to articulate their arguments, clarify their likes, sharpen their dislikes and formulate their positions month by month. Surrounded by a network of allies, the imaginary was made concrete; particularly when your allies were the filmmakers and theorists you were writing about.”[1]

He also edited the German translation of André Bazin’s What Is Cinema?. In 1975, he founded his own film production company, Big Sky Film, which has produced most of his projects. He has directed and to some extent also produced more than 40 (mostly documentary) films. Bitomsky served as the Dean of CalArts’ School of Film/Video from 1993 to 2002.

[1] In Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom? Eds. Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun. Cologne: Walther Koenig, 2010.