THE COMBATIVE PHASE

May 6–June 25, 2017

Thursday–Sunday, 12–6pm

The Combative Phase presents the work of a group of filmmakers with connections to the Media Urban Crisis and Ethno-communications programs, which ran between 1969 and 1973 at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). Working in the wake of the Watts Rebellion of 1965, and other uprisings against institutional racism, economic dispossession, and police brutality in inner cities across the United States, the filmmakers surveyed here evidence a historical period of heightened activism at the intersections of radical film, mass media, and the academy.

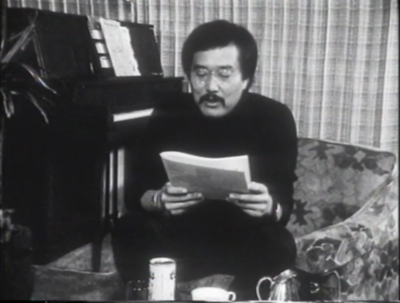

Included are films by Don Amis, Charles Burnett, Ben Caldwell, Larry Clark, Julie Dash, David García and Moctesuma Esparza, Haile Gerima, Alan Kondo, Alile Sharon Larkin, Barbara McCullough, Sylvia Morales, Robert Nakamura, Sandra Osawa, Elyseo J. Taylor, Jesús Salvador Treviño, Luis Valdez, and Eddie Wong.

The Combative Phase attends to a history, but with the understanding that the discursive and material operations active in this history are not finite or detached from present day experience. The Combative Phase proceeds in two parts, beginning with an exhibition of short films and documents running from May 6 to June 25, 2017, and continuing with a protracted and evolving series of screenings and talks running from May 2017 into 2018.

In the years following the Watts Rebellion, UCLA saw a series of structural shifts in response to what became defined within academic and political discourse as “the urban crisis.”[1] These shifts took shape through intersecting but distinct forces, most notably: the committed dissent by members of the student body against discriminatory admissions policies; educational “remedies” extrapolated from the recommendations of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (NACCD) established in 1967;[2] and the mandate towards affirmative action within education, written into the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[3] In 1968, the university established the High Potential Program (HPP), a “special entry program to modify the [composition of the] student population at the University”[4] conceived by a joint student-faculty committee, based on recommendations from the Black Students Union (BSU) and United Mexican American Students (UMAS). Simultaneously, proposals were made towards the founding of an Institute of American Cultures. When inaugurated in 1969, the Institute comprised autonomous centers for Afro-American, Asian-American, Mexican-American, and American Indian studies.

In parallel with these developments, a number of UCLA faculty involved with communications on campus formed a committee to “consider the role of UCLA in translating its interest, knowledge, and activities relating to the urban crisis and the special needs of ethnic minorities into radio and television programming, particularly for educational purposes on a mass basis.”[5] The Media Urban Crisis Committee, under the principal guidance of Elyseo J. Taylor, an assistant professor in the Theater Arts Department, expanded to include student activists, and developed “a curriculum of instruction in film-making for students from the ethnic minorities which would enable and encourage them to use film-making as a tool in community development.”[6] In January 1970, twenty students began the Media Urban Crisis Program, recruited from the High Potential Program and from communities in Los Angeles that reflected the delineations of the four centers within the UCLA Institute of American Cultures. In Fall 1970, the Media Urban Crisis program was renamed Ethno-communications, and became a program within the TV and Motion Pictures Division of the Theater Arts Department.

In its intended form, the Ethno-communications program lasted no more than three years. Its structure however, and the teachings of Taylor and his successor Teshome Gabriel that drew heavily on the influence of Third Cinema, had a significant impact on the UCLA film school and related networks of film and TV production into the late 1970s. The Combative Phase focuses on films produced by those who studied in the Media Urban Crisis and Ethno-communications programs, or those who engaged in the dialogue around the programs, while also foregrounding the figure of the university itself, an institution constituting a particular and historical set of social, racial, and economic relations. The films reflect the intersection of a politics of visibility exercised through institutional reform, and the demand for revolutionary change in the face of the durable political and material stratifications of racial capitalism.

The temporal, spatial, and socio-political frame of the university—and particularly, its attendant conditions of access to education and the means of production—unifies the films exhibited. More significantly, however, the filmmakers here engaged in decentering the disciplining grounds of knowledge and representation embodied by the university, and by Hollywood cinema and the mass media. Their varied films move between forms of documentary reportage and its transmission of history, the scripted construction of vignettes of social realism, and poetic imaginaries. In many cases these films were located in direct discussion with and advocacy for particular seams of political, cultural and social activism, spanning both radical and reformist goals. The films speak to complex transitions between social spaces of protest, the mobilization of cultural identities in tandem with revolutionary politics, and ahistorical logics of cultural nationalisms. The desire for autonomy of production, communication and representation, as well as independence from an oppressive socio-economic system, interweaves with a demand for broad political and cultural visibility, for “distributive justice,” and for social change.

David García and Moctesuma Esparza, Requiem 29, 1970

Alan Kondo, I Told You So, 1974

Charles Burnett, Several Friends, 1969

Sylvia Morales, Chicana, 1979

[1] In May 1968, newly appointed President Charles Hitch presented a paper to the UCLA Board of Regents titled “What Must We Do: The University and the Urban Crisis.” The UCLA staff bulletin at the time reported Hitch as saying: “we need to be blunt and direct. Our nation, our state and our cities are in the grip of a crisis. It is a moral, economic and racial crisis. It is also an educational crisis.”

[2] The NACCD recommended: “Expanded opportunities for higher education through increased federal assistance to disadvantaged students.”

http://www.blackpast.org/primary/national-advisory-commission-civil-disorders-kerner-report-1967#sthash.b4ljd8WJ.dpuf

[3] In her essay “The Racial Limits of Social Justice: The Ruse of Equality of Opportunity and the Global Affirmative Action Mandate” Denise Ferreira da Silva states: “Framing the mandate to bring about equal opportunity, to meet the call for ‘abundance and liberty for all’ and to the ‘end of poverty and racial injustice,’ the document [Civil Rights Act] includes a phrase ‘order such affirmative action’ that animated substantive measures for addressing racial discrimination in all areas, but in particular in employment and education.”

[4] Barbara A. Rhodes, “UCLA High Potential Program 1968-1969,” (Los Angeles: UCLA, 1970), 8

[5] Letter from UCLA Vice Chancellor Paul O. Proehl to members of MUCC, April 23, 1969

[6] Elyseo J. Taylor, “Mass Media and the Social Dialogue,” unpublished paper delivered on September 20, 1976 at the conference “The Role of the Mass Media in Enlisting Public Support for Marginal Groups,” The European Centre for Social Welfare Training and Research, Bellagio, Italy

The Combative Phase would not be possible without the support of the filmmakers; the scholarship of Teshome Gabriel, Chon Noriega, David E. James, Ntongela Masilela, Renee Tajima-Peña, Kara Keeling, Allyson Nadia Field, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, and Jan-Christopher Horak; loans from UCLA Film & Television Archive, Visual Communications, Sankofa Video Books & Café, Women Make Movies, and Milestone Films; and the research and film preservation undertaken as part of L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, a project by UCLA Film & Television Archive developed as part of Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980, and curated by Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, Shannon Kelley, and Jacqueline Stewart.

Yale Union would like to thank Tom Ackers, Don Amis, Thom Anderson, Ben Caldwell, Meghan Conlon, Sarah Diab, Mia Ferm, Abraham Ferrer, Keenan Jay, Jesse Lerner, Rose Mackey, Barbara McCullough, Sandra Osawa, Brandon Phuong, Cinema Project, Lucas Quigley, Kent Richardson, Morgen Ruff, Renate Taylor, Francia Krupa Vahdani, and Sam Wildman; the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, RACC Work for Art, and the Oregon Arts Commission; and our members.

Previous screenings include:

Sunday, May 7, 1pm

The Hour of the Furnaces

Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas

1968, 16mm, 233 min.

Sunday, June 25, 3pm

A Screening and Discussion with filmmaker, Don Amis

UJAMII UHURU SCHULE [Community Freedom School]

Dir: Don Amis, 1974, 16mm transferred to digital video, 9 min.

OPERATION BOOTSTRAP

Dir: Charles and Altina Carey, 1968, 16mm, 58 min.